Essential Cinema Guest Programmer Zachary Brailsford on the Films of Jacques Rivette

Here’s a special contribution from guest programmer Zachary Brailsford. The Essential Cinema series UPSIDE-DOWN AND INSIDE-OUT: FIVE ENCOUNTERS WITH JACQUES RIVETTE begins Thursday January 8.

When considering the length of a film, one most often will find films ranging from roughly eighty minutes to one-hundred and twenty, something it seems most people agree on as a running time for which to take little offense. Some filmmakers, though (Lav Diaz, Bela Tarr, etc.), have pushed the boundaries of what an audience will be willing to sit through in order to more carefully craft and tell their stories. Jacques Rivette, a filmmaker whose works range from eighty-four minutes to around thirteen hours, is one of these filmmakers; his stories build and take the time they need, worrying little for the aggressiveness of an audience so long as the story can be told well and correctly.

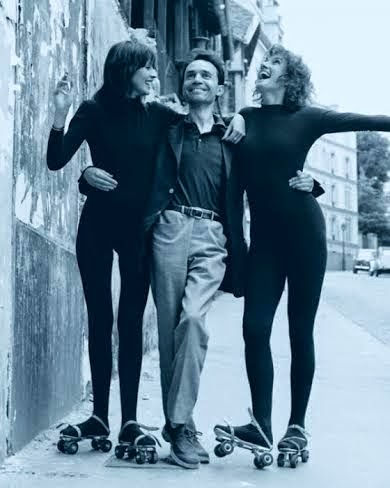

In this series, there are several films of length, most notably CELINE & JULIE GO BOATING (1974) and VA SAVOIR (2001), and the use of duration allows for the films to flow freely between subjects, finding different paths and points of narrative that might otherwise be missed. The films are also very fun. What joy it is to see the opening moments of CELINE & JULIE as Julie (Dominique Labourier) follows behind Celine (Juliet Berto), picking up the items that keep falling out of the other’s bag, all across Montmarte, and then to watch the plot evolve into something more sinister, all the while keeping the light-hearted women at the dead center. Their personalities overcome the toxic nature of the plot that is, in many ways, consuming them. The free-wheeling camera-work only supports the light-hearted nature of the film as a whole, allowing stories to be told by the ever-present protagonists. In a male-dominated medium, it is wonderful and impressive to see a film in which women can grab hold of the narrative and twist it to their own liking without succumbing to the typical gender representations often present in cinema.

Another film in the series, LE PONT DU NORD (1981), is similar, although a little more frightening, as Paris itself becomes a web of dark deeds and conspiracies, and two women strangers, Marie and Baptiste, (mother and daughter Bulle and Pascale Ogier, respectively) must band together in an attempt to break the conspiring nature of the world around them and get out safe and free. It is a film that seems more angry – maybe Rivette was still bothered by the events of ‘68 and how nothing had come of them (OUT 1 [1970] and CELINE & JULIE both are also comments on it), and so he took to looking for hope in seedier people. Both Celine and Julie had been fun-loving women (one a librarian and the other a magician), but Marie, at the start of the film, has just been let out of prison, and Baptiste, a motorcycle-riding punk, flies through the streets and destroys advertisements that represent the fear in modern society plastered on the sides of walls. It is another film that takes its time (it is roughly two hours), and watching the interplay between the two women over the course of the film – how they meet and become partners, and then friends – brings to light the idea that women can and should rely on each other to find favor in the world. Every step they turn there is another man in their way, but they’re stronger than them: they persevere.

Both of these films create images of cultures often not explored in most cinema, and are thus more intriguing for it. Rivette crafted films that would allow a sort of power-struggle in which women never had a “place” they needed to be (and when it seems they do, they usually break out and do their own thing). One of the more radical of the nouvelle vague, he seems to be one of the few of them ready and willing to approach this topic; Rohmer’s films (at least most of his early films) typically revolved around the male perspective coming to terms with the female perspective, but always from the side of men. Truffaut focused on himself through his Antoine Doinel series, DAY FOR NIGHT (1973), etc., and the problems he was causing. Godard did put a focus on women – and in some very great films – but his women were either extensions of himself or, more often than not, Anna Karina, who he seemed to attempt to dominate through the celluloid. Chabrol, who made so many films, definitely was at least able to craft a few about women and their strength, most notably La Cérémonie (1995), although the image he portrays in this film is one of bourgeoisie darkness destroyed beyond repair, making the “hero” women not so much better than the “villain” victims.

Rivette, though, pushed further from narrative and genre conventions, and only Godard was as radical as he. Patterns of editing, story construction, length of scenes and shots: all were handled deliberately with a method for telling stories differently than almost anyone else, and with an ideology that it seemed few other filmmakers (especially men) were willing to get behind. Not to mention that the films themselves are a blast – they move and twist and shed their skin, they include dance and magic and performances, they highlight truths few others choose to highlight, and they do it with a joy and exuberance unmatched. Even in Rivette’s old age was he still able to accomplish these things, as can be seen in VA SAVOIR, THE STORY OF MARIE AND JULIEN (2003), and two more from this series, THE DUCHESS OF LANGEAIS (2007), and AROUND A SMALL MOUNTAIN (2009), although in these four films Rivette chooses to expand the scope of each film’s perspective and give different views on similar topics as he’d always tackled. Rivette tells his stories well, at the length in which he needs to tell them, and he does it better than almost anyone else.